Today I join the ranks of striking university staff*. I thought it was worth taking a few minutes to explain why. Toward the end of last year the University Superannuation Scheme (USS), which provides pensions for some 200,000 university staff (including lecturers, administrative and support staff) published its most recent valuation of its assets and […]

Peshawar Attack, Revenge and the Role of the State

Geeking Out with Louise Krasniewicz

Louise Krasniewicz teaches anthropology classes on zombies, steampunk, science fiction and comic books. As a self-proclaimed geek anthropologist working out of the University of Pennsylvania, we sat down over coffee to swap theories about monsters, the feminization of geek culture and the current state of anthropology.

Krasniewicz began her career with a BA in Anthropology and an MA in Education, Instructional Media and Technology at the University of Connecticut. “Professionally I’ve always jumped between anthropology and technology,” (2014) she tells me, two intellectual threads she has woven into a thoroughly interdisciplinary career. After serving as Media Director for the Albany College of Pharmacy and obtaining a PhD from SUNY Albany, Krasniewicz taught classes at the University at Albany, UCLA and the University of Pennsylvania. Her training in media studies and anthropology has made her acutely aware of the pedagogical potentialities and theoretical frontiers digital media, pop culture and geek anthropology present…

View original post 1,729 more words

Flatulanthropology

I did this with Jon Mitchell

http://allegralaboratory.net/flatulanthropology/

over at the wonderful Allegra

Ontologies – meh

I first became aware of the coming ‘ontological turn’ in relation to the Manchester debate on whether ‘ontology is just another word for culture‘. My objection to ontologies are summed up in that one proposal. Since then we’ve apparently taken an ontological turn following a debate of that name at the 2013 AAA in Chicago.

If the debate is really new to you, in a nut-shell ontology is the philosophy of being and becoming: the existential (but not existentialist) wing of philosophy. As it spreads through anthropology its architects have bilt upon Viveros de Castro’s Amazonian perspectivism which suggests many Amazonians possess such radical alterity, (otherness) through their animistic cosmology (understanding of the universe), as to account for an entirely different ontological reality. For ontologists this is beyond epistemology (the theory of knowledge) as it is about being – not knowing. That Amazonian animists recognise some animals and objects as persons and the ability of these multiple persons to transform across these categories leads to an appreciation of the associated shifts in perception that would accompany such shifts. This is not just a difference in beliefs, knowledge or taxa – this is a difference in their being. Once we recognise the separate way of being in one group the floodgates are open. Multiple ontologies are here.

Recently two blogs – one by the Proctontologist and another an anonymous reader at Savage Minds – dared to be among the first to poke at the ontology bubble. The former has me laughing out loud regularly. I admit to being a fan since an epic rant against ‘the Cambridge clique’ on the Anthropology Matters email list back in 2012 (clearly the same person -surely). Yes – he is mean and rude to friends, colleagues and acquaintances of mine, including at least one who scores a solid 10/10 on any scale by which loveliness can be measured. But I have a juvenile sense of humour (I thought I’d grow out of it upon becoming a dad – turns out 1000+ nappy changes doesn’t stop poo being funny – who knew?) and he has an eye for the ludicrousness that seeps through much of this writing. The second writer (the one on Savage Minds) got me thinking. The two first critiques I’d read sicne the AAA – two anonymous authors. The proctontologist’s anonymity is in a large part troll-armour. The anonymous letter on the other hand seems like something sadder. At post-faculty seminar drinking sessions we are many – it’s time for anti-ontologists to start to share our general sense of ‘meh‘ with the world.

I won’t pretend to have read ‘all the ontology’ – it gives me little pleasure. I know that all of these criticism have counter-punches waiting for them – I’ve heard and read most of them but they’ve not swayed me. So – a very rough outline of my grumblings follows:

- It’s culture. It was there from the beginning for me. I understand that culture is a loaded term – but taking it to be fluid, contested, social constructed – it’s the analytical category that stands for the short hand for the stuff of anthropology. Yes – Amazonian perspectivism is more than belief – there are practices and material things woven into these webs – but ontologists don’t add anything to my understanding. If anything it introduces an intangible black box at the heart of some people and cultures with claims made that these things are unknowable for outsiders. If it’s not culture it’s habitus or doxa or some other synonym we use to avoid the word culture. It’s culture. Meh.

- Social change – yes there is talk of transformation, vectors and becoming – but ontologies are clearly more frequently deployed to illustrate deep-lying differences of the ‘they do X’ variety. Doesn’t sit right for me.

- They are X. There’s an awful lot of ‘they’ in ontological writing. Too much homogenisation for my liking. Hard to talk about the collective being of a group of people without homogenising.

- Cultural relativism redux. It’s just rehashing cultural relativism debates in a new shiny philosophical package. We got past this. There’s a side order of the Sahlins/Obeyesekere debate in there too – with accusations about the unknowability of the mind of ‘the other’. It just seems like trudging back over old ground for the sake of arguments that aren’t actually derived from informants but from our own desire for a bit of a kerfuffle. Which brings me to…

- Puppetry (critique nicked from Andrew Irving). Ontolgists are projecting philosophically nuanced ideas onto other people(s) to make them dance for anthropologists to have a conversation about anthropology. This is not about our informants – it’s about us. Meh.

Having said all this – I am fully prepared to be convinced. I could be wrong. It just seems to me that every time this debate starts up down the pub we get further and further away from anthropology and further into philosophy. Yes it might frame a debate about understanding differences very well – but unless it helps me understand those differences (and similarities) then I’m not going to jump on board.

The Playlist

The Fieldwork Playlist – 25/10/13

The Playlist

Venue: Room 137, Richard Hogart Building, Goldsmiths

9:00-9:30 Registration

Panel One –Fellowship: Chair Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg

9:30-9:45 Introduction

9:45-10:00 Simon Procter – ‘Help Me Make It Through The Night’

10:00-10:15 Louise Laverty – ‘Your Man’

10:15-10:30 Cassandre Balosso – ‘Jota des Vermar’

10:45-11:00 Discussion

Coffee break 11:00-11:30

Panel Two –Alienation? Chair: Helen Cornish

11:30-11:45 Gavin Weston – ‘Oh Señor…’

11:45-12:00 Will Tantam – ‘British Love (Anything for You)’

12:00-12:15 Jennifer Parr – ‘The Lady of Shallot’

12:15-12:30 Discussion

Lunch/Interlude – 12:30-1:30

(Video presentations from Patrick Alexander – ‘Dare’; Samantha Bennett – ‘Fan It’, Julie Jenkins – ‘Africa’; & Stephen Van Wolputte – ‘Indaba’).

Panel Three –Evocation Chair: Mark Lamont

1:30-1:45 Catherine Allerton – ‘Sahabat’

1:45-2:00 Marlene Schäfers – ‘Dewran’

2:00-2:15 Mark Jamieson – ‘Wild Gilbert’

2:15-2:30 Discussion

Coffee break – 2:30-3:00

Panel Four – Performance Chair: Dominique Santos

3:00-3:15 Ole…

View original post 6,128 more words

The Gruffalo: A Structuralist Analysis

It’s finally happened. I’ve now read certain children’s books so many times that I’m starting to internalise them. First it was Alison Jay’s excellent I Took the Moon for a Walk. Now it’s The Gruffalo.

With an 11 month old I rarely get all the way through before the book is picked up and chewed, he starts to turn the pages back towards the beginning, or he just gets up and leaves. But what strikes me most about the book when I do make it all the way through is the beautiful symmetry to it. The first line is echoed in the last. The three meetings (with the fox, the owl and the snake) are played out in reverse order in the second half. It all tilts around the mid-point meeting with the Grufallo. It is so well structured it is a thing of beauty.

Now I can’t help but feeling that this echoes something familiar as an anthropologist. The ingredients of story – the symmetry and structure – make little Levi-Straussian bells go ding-a-ling in my head. The symmetry, while perhaps stripped down (it is for kids) echoes Levi-Strauss‘ analysis of the trickster myth. The little mouse being a Prometheus character.

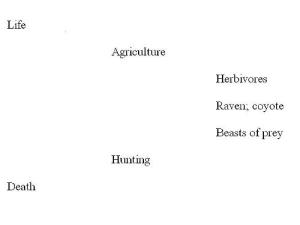

The story is in essence about a mouse who uses cunning to overcome three animals and a Grufallo who all want to eat him. So on the way to the apex of the story he is fearful of being eaten and must use his story-telling cunning to convince the fox, owl and snake that he himself is to be feared and therefore not eaten. The story-telling device he uses is to invent a horrid monster – the Grufallo. The twist then comes that when he gets past the three carnivorous animals he discovers the Grufallo really exists. He then walks back through the forest with the fear of each of the animals he’d passed earlier confirming his fearfulness to the Grufallo. His declaration that his favourite food is’ Grufallo crumble’ echoes earlier threats to the animals that the Grufallo’s favourite food is ‘roasted fox’, ‘owl ice cream’ and ‘scrambled snake’. It is also the final straw that sees the Grufallo flea in fear and the mouse left free to enjoy eating a nut.

So what we have here is the Levi-Straussian binaries of feared: fearful, prey: hunter, herbivore: carnivore, and reality: make-believe. The story is one of transformation through storytelling. As Edmund Leach notes of Levi-Strauss’ structuralism – it’s best to visualise these binaries in regards to triadic relationship – the transformative process being the third side to the triangle. Through storytelling the mouse is transformed from prey into hunter, from herbivore to carnivore, from the fearful to the feared. He is the trickster – achieving all of this through his wit and storytelling ability. But in trickster myths regarding fire, the pivot of transformation occurs when fire is stolen. Here, rather than it being fire, the power the mouse acquires seems to be the ability to construct reality through story. The Grufallo is brought into existence through his story-telling. While often there is a punishment received by the trickster in such myths – this is a lovely gentle children’s story. Here the mouse defeats the Grufallo. His reward – a return to his natural state as herbivorous – but in a new life without fear.

‘The mouse took a walk in the deep dark wood. The mouse found a nut and the nut was god.’

I may have over-thought this.

A guide to pronouncing your anthropologists

Having stumbled across two names in one week that I’d been mispronouncing (Loic Wacquant and Walter Benjamin – I’ll get back to them in a moment) it strikes me that there’s no place online where all the commonly mispronounced names of anthropologists and key thinkers from kindred disciplines are gathered with the correct pronunciation given. I have trawled the internet for seems like the most-trustworthy pronunciation of each (is the auhtor there? Do they correct the person? etc…). This is not without the potential of my having got one or more wrong. I also accept that there is variability in the pronunciation of names (I spent a year as Gabino in Guatemala), but this is the best guidance the internet has to offer (that I could find using my rudimentary skill set).

The problem of academic mispronunciation is one based on thankfully diverse backgrounds of academics. There are academic lineages of mispronunciation – poor pronunciation passed on from teacher to students (who then become mis-teachers themselves). The key problem seems to be reading a person’s work before you’ve heard there name pronounced correctly. The opportunity to re-read the name incorrectly in your head for several hundred repetitions is a foolproof way of guaranteeing sounding idiotic at some point in the not too distant future.

Of the two I’d been mispronouncing (Benjamin and Wacquant) neither is an anthropologist strictly speaking – but both transcend categories in ways that make them anthropological-ish. I’ve been saying Walter Benjamin for years then in a conversation I found the other speaker pronouncing it BenYamin in each sentence that followed mine. It took me a moment to realise I was being politely corrected. On reflection – of course it is pronounced with a Y sound. Any knowledge whatsoever of the man would tell you that – yet since being corrected I’ve noted that more people mispronounce it than pronounce it correctly. If you’re still in doubt here’s Judith Butler (who I’ll make a sweeping assumption would do it properly) talking about him.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dtRwOkGV-B4

Wacquant had me over-pronouncing the Q – it’s much softer. More like Whack-on:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KoumuRRwOqY (3:38 in he’s introduced)

Confirmed here: http://www.forvo.com/word/wacquant/

OK – so who are the others that should be discussed here. Let’s start with the big-guns. Bronislaw Malinowski is ambi-pronounced. Is it a W or an F sound?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ln2X8rohtak

That would be Bronislav Malinofski then – Confirmed here: http://www.forvo.com/word/bronis%C5%82aw_malinowski/

Is Clifford Geertz pronounced Geer or Gur? Well this one might annoy many of my friends who a stubborn users of the EE sound – but it’s pronounced Gurtz:

http://www.forvo.com/word/clifford_geertz/#en

It even makes it’s way onto Wikipedia’s list of names that are pronounced counter-intuitively.

If Melvyn Bragg can be believed Claude Levi-Strauss is pronounced Levee-Strouse. Those are the main forefathers of the discipline whose names are mispronounced – what of more recent bete noires?

Arjun Appadurai is remarkably phonetic compared to some of the messes that students get into with his name. Ar-Jun Apaduri in essence:

http://www.forvo.com/word/arjun_appadurai/

Speaking of bete noires – Napoleon Chagnon does appear to be Chanyon. Again – another I seem to be guilty of mispronouncing. For Adam Curtis’ pronunciation see 22:45 in on this video (and then watch the rest of the film because Adam Curtis is awesome):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZuezx18jEI

It does appear I’ve been mispronouncing Philipe Bourgois’ name too. Rather than being pronounced like bourgeois it is pronounced (1:18 in) Borg-wah. Now I’m pretty sure I’ve corrected students on that one incorrectly – my apologies former students. My sincerest apologies.

One I’ve had to look up historically is Gananath Obeyesekere. It’s pronounced Ober-seecra.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PEeaUGDw1PY

I apologies for my ham-fisted attempt at doing this without using phonetic characters – this seemed to be a clearer way of doing it.

Who else needs to go on this list?

Two Tone Anthropology: Towards a Journal of Frivolous Anthropology

With a conference finished and my last board of examiners meeting now over it’s now time to move on to the usual summer activity of writing. As I sit down to start contemplating what needs my attention, my anthropological proclivities become clear. Articles and papers are underway covering the spread of collective violence, vigilantism and security, and the role of hearsay in the causation of violence. Serious stuff – and necessarily so. But these sit alongside articles on fictional anthropologists in films and Batman. I’ll also be on a panel next week with Phoenix Jones, Seattle’s real life superhero. While there’s a serious side to these other issues – they are of a very different type. So, not for the first time, I’m having the thought – ‘I’m a two tone anthropologist’.

I think anthropology is at its strongest when its engaging with social problems. I may love functionalist explanations – they are anthropology at it’s most elegant – it makes the world of social interactions seem sensible and tidy. The reason functionalism became a dirty word is because most social systems are messy – inequalities, abuse of power, discrimination, violence and illness are ubiquitous. The world would be better with less of each of these things. While these problems are all too big for anthropologists or anthropology to ‘solve’, the suffering they cause make them the most worthy issues on which to spend our time. Getting to grips with the complexities of the intertwined forces and practices that make up these social problems is of value beyond the boundaries of our discipline. Understanding the causes of inequalities and suffering, or, building on this, understanding the imperfections of the structures set up to minimize these things – that’s what I think the largest amount of socio-cultural attention should be directed towards.

Contrarily anthropology is most fun to play with when the stakes are low. When it’s just pushing anthropological ideas into odd realms. When there are no informants whose safety we have to worry about. When we can just playfully apply anthropological theories to interesting areas. Once you’ve had that anthropological epiphany (that magical moment, generally at some point in your undergraduate degree, when you realise that anthropology has started to make you think differently) you start doing it by accident. Friends will ask you a straightforward question and 10 minutes later you’ll have gone deep into Gell-ian understandings of objects or talking about Geertzian winks. The occasional chance to run with these thoughts a bit further and in print (or in a blog) seems to me the perfect antidote to the depressing nature of reading about suffering, inequality and imperfect systems.

I’m pretty sure I’m not alone in this (although I note that many anthropologists deliberately separate their work and play) but I think two tone anthropology is the way forward. Blogs are a very good repository for some of these musings – but wouldn’t it be nice to get our working out for these things properly scrutinised? Wouldn’t it be nice if some of our peer-reviewing was of anthro-fluff that correlates with the fluff we’re interested in? Wouldn’t it be good to have a journal dedicated to anthropological curve-balls? This is something I would like to see – we need a Journal of Frivolous Anthropology!

10 ways life of anthropologists changed in last decade

Ten years ago this summer I started my PhD at Sussex. I have a predilection towards a good listy blog – so I thought I’d look back over the last decade at how the lives of anthropologists have changed in this time: five ways it’s got better, five ways it’s got worse.

5 ways it got better:

1. Google

Like all powerful tools Google has its drawbacks. It contributes to one of the ‘Ways it got worse’ list that follows. It is also complicit in surveillance, annoying advertising, tax evasion and other problematic practices. But in terms of making the life of anthropologists easier or more productive it is has had more impacts than I’ll manage to think of here. Literature searches (in Google search or Google Scholar) have become so much easier tat it is easy to forget the meandering path from one book to the next through a trail of references that I used to go through as an undergraduate.

Beyond searching for key words the ‘cited by’ and ‘related articles’ functions in Google Scholar let you follow paths of connectivity that shave days off writing papers and reading lists. Google image search makes jazzing up wordy Powerpoints immensely easy. You can find direct quotes within seconds rather than having to trawl though books, find news stories when you can’t remember where you read X. You can find phone numbers and email addresses details of grants and deadlines; unearth teaching resources and films. In 2013 I find it hard to envision life without Google.

2. Digital recording devices

Bulky dictaphones; awkward tapes; posting tapes to relatives; paranoia about the demagnetising properties of airport metal detectors; inability to easily back up recordings; turning tapes over at inopportune moments in interviews – these are all problems of the past.

English: Audio levels shown on a Zoom H4n while recording Deutsch: Lautstärkeanzeige des Zoom H4n bei der Tonaufnahme (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

New abilities to record, store and copy days or weeks worth of interviews and films digitally has made audio and visual recording easier, less burdensome and less time consuming while also increasing the audio and sound quality available to ethnographers everywhere. Coupled with programmes like Nvivo that offer the ability to file, share, annotate and code this data, digital recording devices are offering opportunities to change the way we make field notes and conduct interviews.

3. Electronic journals/books/blogs

The rise in online journals and online libraries like JSTOR has changed the way that I use journals entirely. Aside from the journals sent to me through the post due to membership of organisations or my own publications I can honestly say I have not picked up a hard copy of a journal in either of my last two jobs. That’s over three years in a post-hard-copy world. While books are clearly going in a similar direction there is still something tactile about an ethnography or an edited volume that draws me towards them whereas endless photocopying and massive filing cabinets are not something I miss in the slightest. The transition from laptops to tablet PCs is clearly going to accentuate this digitisation of reading material and as a result of that teaching will doubtlessly change too.

This as been accompanied by the rise in blogs as a new medium which bypasses the glacial pace of anthropological publishing. For me, coverage of the Human Terrain System was a milestone in anthropology. The frustratingly slow pace of research, writing, submission, editing and publication resulted in a chasm at the heart of anthropological writing while anthropology was in the news more prominently than it had been in years. Blogs on the topic were immediate and accessible. Starting to write this blog is an acknowledgement that this medium has advantages over other forms of writing. Alongside new moves towards open access, this is part of a complete overhaul of in the written forms anthropology takes that will doubtlessly see more changes over the next decade.

4. Turnitin

Whether you’re a marker or a markee – Turnitin has changed the system of submitting work and giving feedback massively. There are many grumbles about not being able to mark in your garden or on a train to be had. There also seems to be accompanying ratcheting up of scrutiny of marking procedures that accompanies the introduction of a new system – but that’s disgruntling but for the best. But the big improvements that Turnitin brings with it are A). a digitisation of marks and grades that makes record keeping more accessible, less demanding of dusty cupboards and more fitting with globalised student and staff movements. B). It makes plagiarism very easy to prove (in many cases). A decade ago it used to take detailed knowledge of key texts and some real detective work to prove plagiarism. Just a few years ago it used to take the endless googling of suspicious passages, dropping one word, then another, then another to try and figure out which one word had been thesaurused . Putting a case together against a student took a real act of will. I once lost three days to a particularly bad batch of essays. Now Turnitin does it for you and I’m happy.

Willful plagiarism at any stage in your academic life deserves punishment. It makes a mockery of those who play fairly, those who took their time to teach you and those whose work you’ve stolen. Turnitin helps me catch you. This pleases me.

5. Finding our way out of postmodernism

When I first started my PhD social anthropology felt a bit stuck. Foucauldian post-structuralism, Strathernian complexity, Baudrillardian linguistic uncertainty were at their peak. The only areas in anthropology where anybody seemed able to say anything at all certain was in critiquing others – either within the discipline or outside it. While this lead to prosperity in anthropology extending into development, medicine human rights and other areas it perhaps wasn’t the best thing that ever happened to ethnography. An unbearable amount of ethnographies became introverted – representing their argument as limited to their own specific view of one particular place. It felt like cross-cultural comparison was dying. While we’ve kept bits of this (I wouldn’t want it any other way) I feel much more comfortable that we’ve got more meaningful things to say than just criticism.

5 ways things have got worse

6. Competition for jobs

I was speaking to a Professor of anthropology not long ago (the British type not the American ‘all lecturers are professors’ type) and he told me that he’d got his first lectureship with just one article in print. That would be unthinkable now. There has been an escalating arms race of early career publications (partly driven by my next bugbear) where entrance level academics are expected to have an array of impacting publications in print and enough on the burner to demonstrate you’ll be fruitful for years to come. The main source of this arms race has been the masses of DPhil students being processed by departments across the country and throughout the world. With most institutions having a number of PhD students at a similar level to the number of staff in the department the creation of anthropologists outnumbers the number of new teaching and research positions arising each year. While I don’t expect every DPhil to want to become a lecturing anthropologist, I’ve been through the ringer myself and have been watching as friends who are excellent researchers and teachers have struggled (and are still struggling) to find permanent jobs within higher education. Associate tutors/visiting tutors/teaching fellows and other teaching-only positions are often poisoned chalices – massive teaching loads preclude publishing in a publishing-centric career stream. While some departments and supervisors have realised this and are sending DPhils into the world prepared for these eventualities the harsh realities often come as a massive surpise to those entering the melee. It certainly did for me.

2.REF

In much the same way that university staff increasingly critique A-level syllabuses (for non UK-reader replace A-level with another pre-university assesment – complaints seemt o be similar elsewhere) for teaching students ‘how to pass tests now’ rather than teaching them ‘how to learn’ – the REF (Research Excellence Framework – the artist formerly known as the the Research Assessment Exercise) has become about playing the game. It’s not new, it’s just getting more refined. It exacerbates the above problem for junior academics, it leads to the destabilisation of departments as everyone tries to get the best roster of academics their budget can stretch to leading to mass movement. I know some sort of assessment is necessary in the current climate of free market competition between universities – but I’m sure it can be done better than this.

3.Student fees

The introduction of student fees in the UK is a hideous thing at all levels. A prosperous society should invest in its intellectual future. Students have suffered (and will suffer the burden of debt for years to come) ore than staff – but we feel the pain to. With recruitment numbers dropping – there will be aftershocks felt across academia in the not too distant future. But for the time being the main change is that students are increasingly demanding their money’s worth. Rightly so. But when combined with the increased pressures posed by REF on research we’re being squeezed from both sides. This sucks.

4. Ontologies

The rise in talk about ontologies and multiple ontologies is just euphemising what we used to call culture and cultural relativism. This annoys me immensley and I will more than likely go on a rant about it in the not too distant future. Viveros de Castro is fantastic – perspectivism is interesting – but the ontological turn resulting from his work is Emperors New Clothes-like. I may be wrong – I have been before – but I sense a backlash coming.

5. Student plagiarism

It’s not all sunshine and lollipops emanating from Google. The temptation to cobble together essays from websites and texts has also been facilitated by the search engine. Essay writing services abound. Turnitin offers Writecheck – a sister product that allows students to check if they’ve rejigged the work of others enough to make it undetectable.

While some aspects of plagiarism, collusion and cheating become easier to catch – others are being facilitated by new technology. On one level cheating is probably an effective life strategy and some might even want to reward it – but I happen to think that a level playing field is important. Sadly these services and technologies are run by people who want to make a profit. Those who can afford to cheat have more opportunity to do so. This seems doubly unfair and therefore doubly disgruntling.